What the real estate market in Portugal will look like in 2026 after the golden visa ends

Portugal’s real estate market is entering uncharted territory. For over a decade, the so-called Golden Visa program—which granted residency permits to foreign investors purchasing property above certain price thresholds—shaped the nation’s housing landscape in ways both visible and invisible. Now, as this policy winds down, the country faces a fundamental reckoning with what comes next.

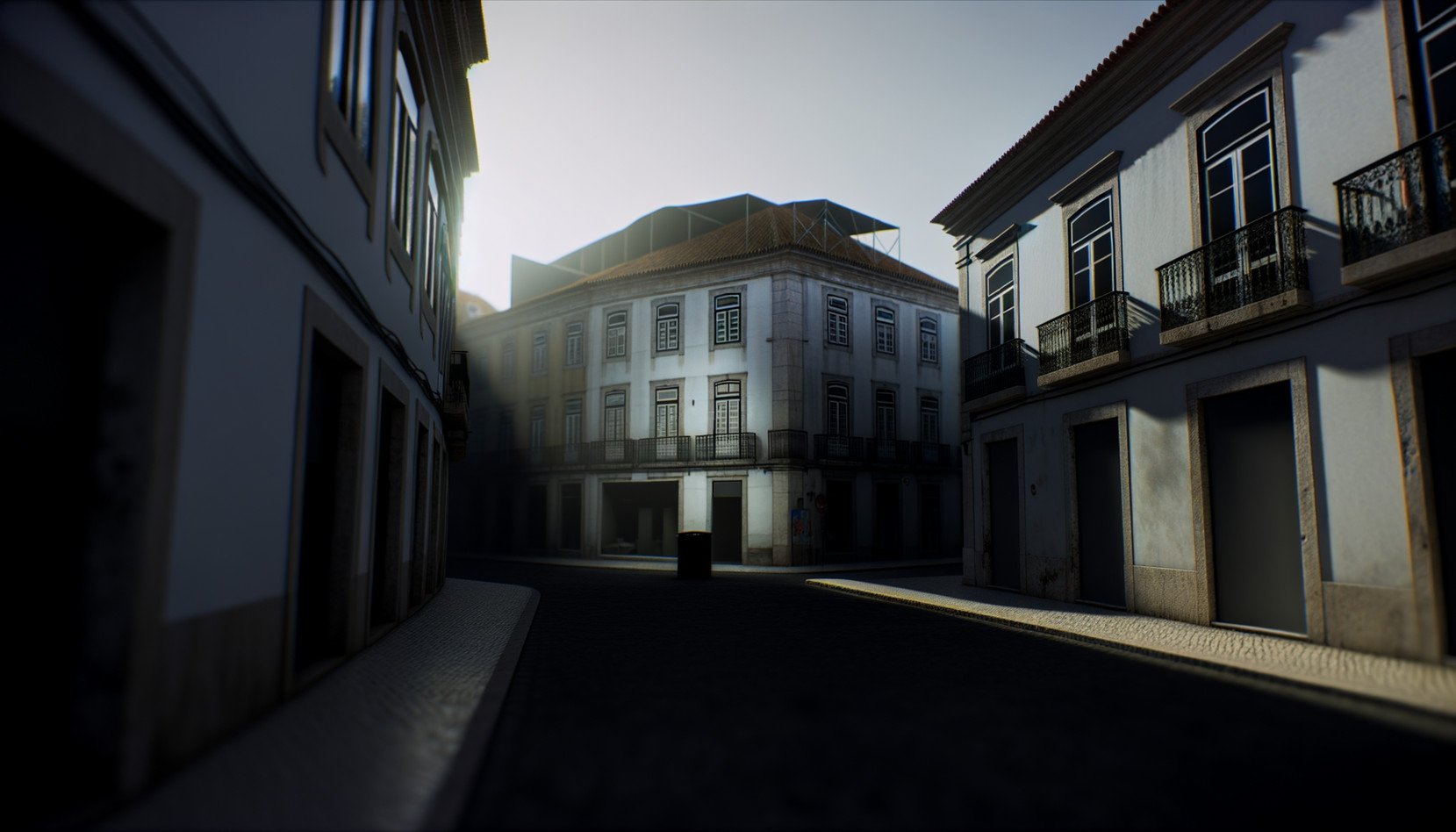

The Golden Visa era fundamentally altered how Portugal’s property market functioned. Foreign capital flooded in, particularly from China, Russia, and the Middle East, driving prices upward in desirable coastal areas and Lisbon’s historic neighborhoods. Local residents found themselves priced out of their own cities. Entire blocks transformed into investment portfolios rather than living communities. The program achieved its economic objectives—generating significant government revenue and attracting foreign direct investment—but left behind a housing market increasingly divorced from the realities of ordinary Portuguese workers and families.

The question now is not whether this transition will happen, but how disruptive it will be. Property markets don’t simply reset when policies change. They absorb shocks through a cascade of effects: declining valuations, reduced construction activity, shifts in investment patterns, and inevitable social consequences for those caught in the middle.

The Investment Momentum That Built a Bubble

Between 2012 and 2024, the Golden Visa program attracted roughly €5 billion in real estate investments. This wasn’t marginal capital—it represented a substantial portion of Portugal’s property market activity, particularly at the premium end. Foreign investors weren’t necessarily seeking to live in Portugal; they were seeking asset appreciation and residency benefits. This distinction matters enormously.

When investors buy for returns rather than use, market dynamics shift fundamentally. These buyers typically hold properties longer, accept lower rental yields in exchange for capital appreciation, and prove less sensitive to local economic conditions. They create artificial demand that distorts pricing signals. A two-bedroom apartment in Baixa Pombalina or along the Cascais coastline commanded prices that bore little relationship to what local incomes could support.

According to Eurostat data on European housing markets, Portugal experienced one of Europe’s most dramatic price increases over this period, with residential property values rising approximately 180% in major urban centers while wage growth remained substantially lower. This disconnect between asset prices and economic fundamentals rarely ends smoothly.

When Foreign Capital Withdraws: The Adjustment Phase

The Golden Visa program officially ended in September 2023, though existing applications continued processing. What happens when a significant source of demand suddenly vanishes? History provides limited comfort. Markets that relied heavily on foreign investment—from Dubai’s real estate sector to Spain’s coastal properties during its own boom—experienced painful corrections.

The adjustment doesn’t affect all segments equally. Prime locations in Lisbon and Porto may hold value better than secondary markets. But developers who planned projects around continued foreign investment demand now face altered economics. Construction timelines may extend. Some projects could stall entirely. Landlords expecting capital appreciation now confront the possibility of flat or declining values.

Rental markets face their own complications. The Golden Visa created a shadow rental market—properties owned by foreign investors but available to tourists or long-term tenants. As these investors reassess their holdings, some properties may exit the rental stock entirely, further tightening an already constrained supply for ordinary renters.

The Rarely Addressed Social Displacement Challenge

While economists debate market mechanics and property valuations, a more urgent human reality remains largely unexamined: where do people actually live when their neighborhoods transform into investment vehicles? The Golden Visa era displaced entire communities through economics rather than policy. Young families left Lisbon for smaller cities or suburbs. Generational residents sold family homes because they couldn’t afford renovations in neighborhoods suddenly valued for international appeal rather than livability.

The post-Golden Visa period offers an opportunity to reverse some of this damage, but only if Portuguese policymakers make deliberate choices. Without intervention, market forces alone won’t suddenly make housing affordable. Price declines in luxury properties don’t automatically translate to affordable housing for middle-income Portuguese workers. That requires proactive policy responses—whether through zoning reform, social housing investment, or other mechanisms.

“The challenge now is ensuring that any correction in luxury property markets translates to improved affordability for local residents, rather than simply shifting where foreign investment flows” – Housing policy analyst monitoring Southern European real estate transitions

Construction and Development: The Uncertain Pipeline

Portugal’s construction sector expanded significantly during the Golden Visa years. Developers launched projects betting on continued strong foreign demand and capital appreciation. Now these same developers must reassess assumptions about market fundamentals, buyer profiles, and reasonable return expectations.

Some projects will proceed with revised expectations. Others may be abandoned or significantly scaled back. Vacant construction sites littering cities send powerful signals about market confidence. For workers in construction, periods of project uncertainty create employment volatility. For neighborhoods, half-finished developments can become eyesores for years.

Regional Winners and Losers Beyond Lisbon

The Golden Visa concentrated capital in Portugal’s most glamorous addresses. But secondary and tertiary markets also experienced spillover effects—Madeira, the Algarve, and Porto all benefited from investor interest. These regions now face a different challenge. Without the premium price support that attracted initial foreign investment, what actually sustains their property markets?

A city like Covilhã or Guarda might discover that post-Golden Visa conditions actually create opportunities. If Lisbon properties decline to more rational valuations, some Portuguese buyers and younger families might choose to live there rather than relocate abroad. But this requires functional local economies, quality infrastructure, and genuine livability factors that pure investment demand never requires.

Portugal’s real estate market enters 2026 in transition rather than crisis, though the distinction remains provisional. The outcome depends substantially on policy choices not yet made and economic conditions not yet determined. The end of the Golden Visa represents an inflection point, a moment when markets recalibrate and communities have perhaps one window to shape outcomes rather than simply absorb them.